There has been a lot of talk recently about the importance of carbon in forests. Carbon dioxide is the leading source of greenhouse gas emissions, resulting from burning fossil fuels for transportation and energy and producing electricity, among other sources. Trees sequester carbon dioxide from the air and turn it into carbon stored in wood. As a result, healthy trees and forests increase carbon storage and avoid greenhouse gas emissions. Many entrepreneurs and policymakers have sought to capitalize on these “natural climate solutions” that trees provide by offering payments to landowners for the carbon benefits their trees provide or by offering incentives to implement “climate-smart” forest management practices.

Forests are a net sink of carbon in the United States, meaning they absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they emit. Recent analysis from the USDA Forest Service estimate that in 2019, forests and harvested wood products offset more than 11 percent of all of the greenhouse gas emissions.

Even with all of the major forest disturbances that have recently occurred, such as wildfires, blowdowns, and insect and disease outbreaks, forests in the United States continue to store more carbon. The total amount of carbon stored in US forests has ranged from 50,913 million metric tons in 1990 to 55,993 million metric tons in 2019. Foresters and loggers may often deal with carbon in the live trees, but trees are not the only component where carbon is stored in forests. In addition to live trees (including the stem, branches, and roots), carbon is also found in pools such as the deadwood (standing snags and coarse woody debris), litter, and soil.

The carbon stored in harvested wood products (HWPs) is also included in estimates of forest carbon. This is important because it counts the carbon benefits of wood that the forest products industry provides. For example, a mass timber building designed and built with wood will “lock up” the carbon in those trees, storing the carbon for decades or even centuries later. This has tremendous benefits when compared to building with other more greenhouse gas-intensive materials such as concrete or steel.

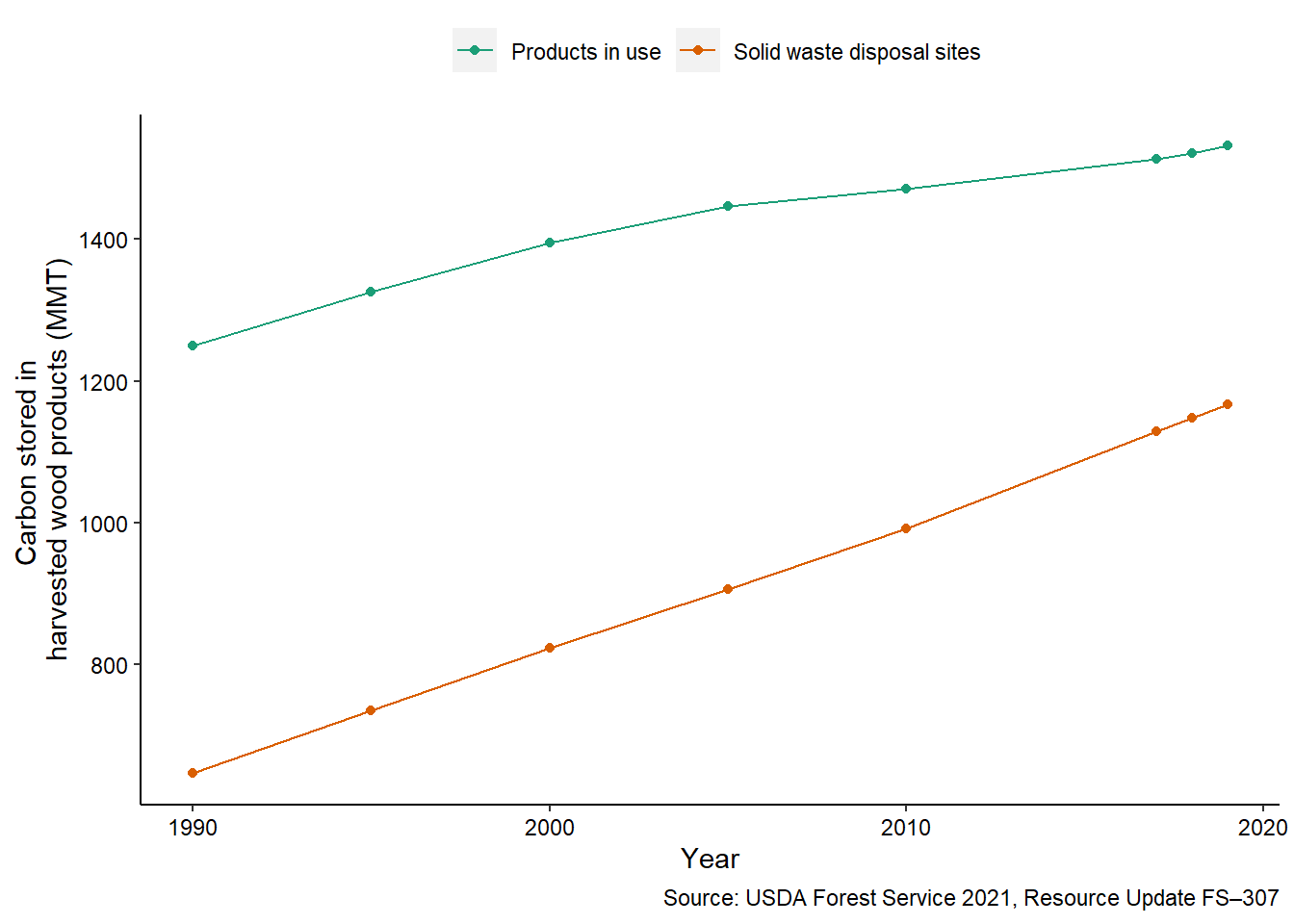

Carbon stored in HWPs includes estimates from two primary sectors: products in use and solid waste disposal sites (SWDS). Harvested wood products include all wood-derived products such as furniture, plywood, paper and energy uses. Wood that is harvested remains in use in products for different lengths of time: think a piece of paper with a short life cycle compared to a utility pole that can serve its use for up to a century. In a complete life cycle of carbon accounting, different wood products vary in how fast or slow they decay, related to how much potential they will ultimately emit back to the atmosphere.

Solid waste disposal sites also store a tremendous amount of wood, most notably when wood products reach the end of their life cycle. The sites include landfills and dumps where wood is slowing decaying for decades. For example, a common metric is to assume that the half-life for wood in a landfill is 29 years. That is, if would take 29 years for half of the biomass of the wood to decay.

Estimates for the carbon stored in HWPs in use and SWDS have increased steadily since 1990. In the USDA Forest Service’s recent estimates, these pools stored 1,532 and 1,167 million metric tons of carbon in 2019, a 23% and 81% increase since 1990:

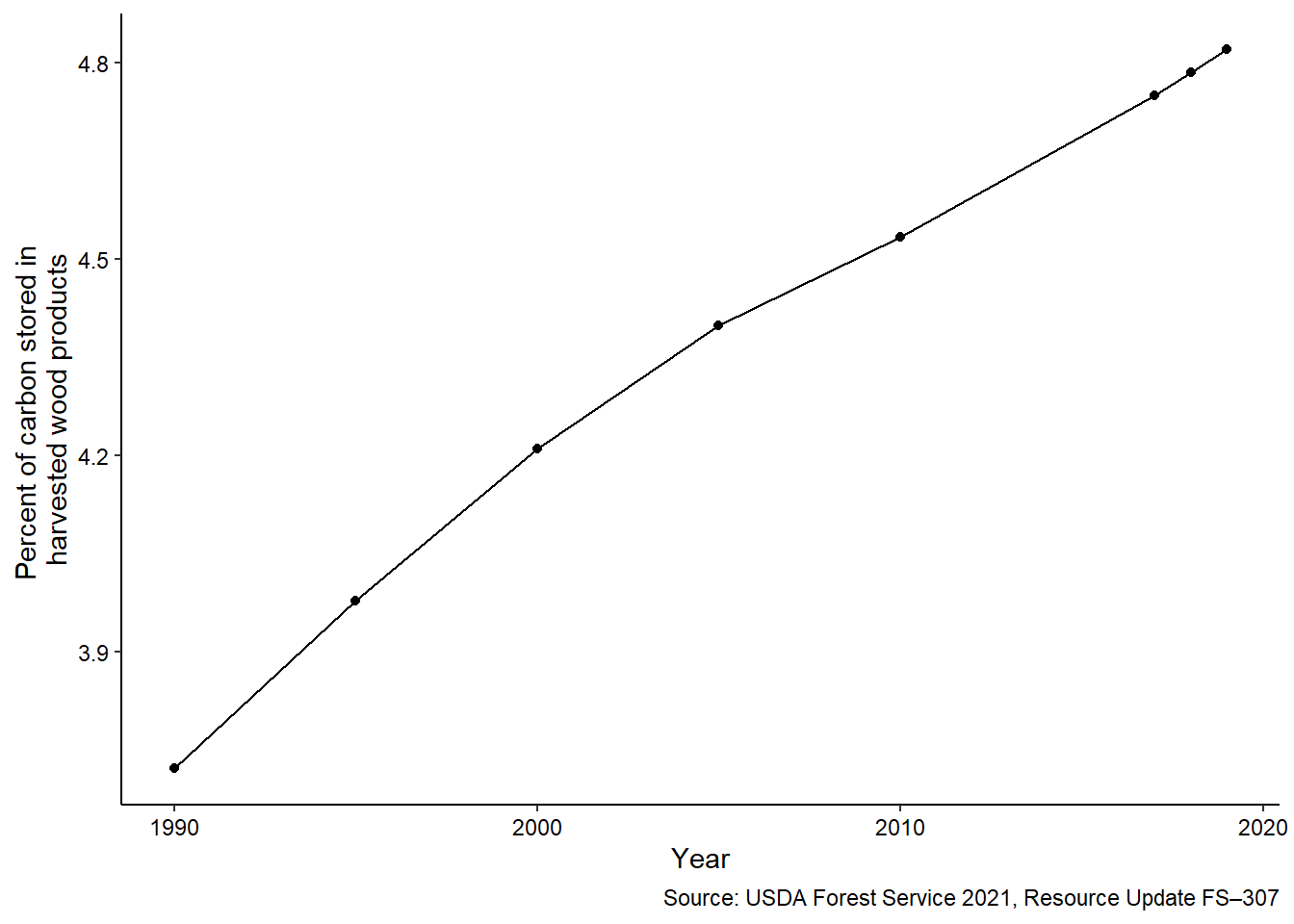

The carbon stored in HWPs has outpaced growth increases in the forests themselves. The amount of carbon stored in forests is much greater than that stored in HWPs, yet growth increases in forests have increased by 10% since 1990. Because of this, carbon stored in HWPs has contributed increasingly more to the total carbon storage across the US in recent years when measured on a relative scale.

In 1990, HWPs represented 3.7% of all forest carbon stored in the US. In 2019, HWPs represented nearly 5% of all carbon stocks:

In the US, HWPs have long been a net sink for carbon. Recent increases in the contribution of HWPs are the result of a productive economy over the last several decades. While economic downturns such as the Great Recession turned HWP pools in the US briefly into a source rather than a sink, production and use of HWPs quickly rebounded. As consumers continue to use products derived from wood, the carbon benefits of those products will continue to be valued into the future.

Despite many recent challenges to the forest products industry including mill closures and downsizes related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the increasing role of HWPs in the US’ “carbon portfolio” is a bright side that should make its workers proud. The increased use of HWPs represents a trend in the US: building and using forest products provides a number of environmental benefits. In particular as wood is being used in manufacturing to replace more greenhouse gas intensive materials like concrete and steel, the forest products industry can point to the carbon and climate benefits of building with wood.

–

By Matt Russell. Email Matt with any questions or comments. Sign up for my monthly newsletter for in-depth analysis on data and analytics in the forest products industry.